| Read on LessWrong |

The problem

This tweet recently highlighted two MATS mentors talking about the absurdly high qualifications of incoming applications to the AI Safety Fellowship:

Another was from a recently-announced Anthropic fellow, one of 32 fellows selected from over 2000 applications, giving an acceptance rate of less than 1.3%:

This is a problem: having hundreds of applications per position and having a lot of those applications be very talented individuals is not good, because the field ends up turning away and disincentivising people who are qualified enough to make significant contributions to AI safety research.

To be clear: I don’t think having a tiny acceptance rate on it’s own is a bad thing. Having <5% acceptance rate is good if <5% of your applicants are qualified for the position! I don’t think any of the fellowship programs should lower their bar just so more people can say they do AI safety research. The goal is to make progress, not to satisfy the egos of those involved.

But I do think a <5% acceptance rate is bad if >5% of your applications would be able to make meaningful progress in the position. This indicates the field is going slower than it otherwise could be, not because of a lack of people wanting to contribute, but because of a lack of ability to direct those people to where they can be effective.

Is more dakka the answer?

The Co-Executive Director at MATS, Ryan Kidd, has previously spoken about this, saying that the primary bottleneck in AI safety is the quantity of mentors/research programs, and calling for more research managers to increase the capacity of MATS, as well as more founders to start AI safety companies to make use of the talent.

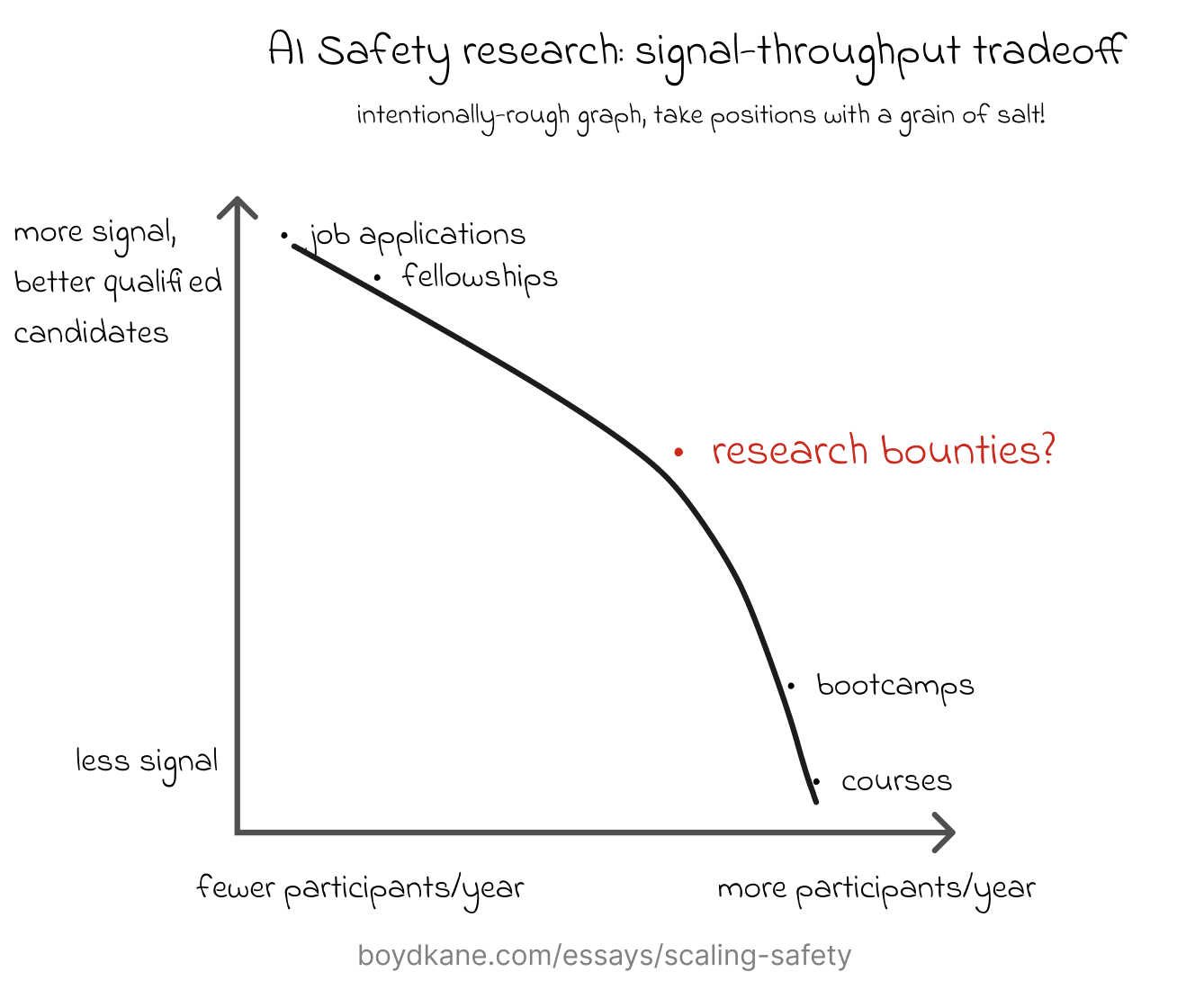

I have a slightly different take: I’m not 100% convinced that doing more fellowships (where applicants get regular 1-on-1 time with mentors) can effectively scale to meet demand. People (both mentors and research managers) are the limiting factor here, and I think it’s worth exploring options where people are not the limiting factor. To be clear, I’m beyond ecstatic that these fellowships exist (and will be joining MATS 9 in January), but I believe we’re leaving talent on the table by not exploring the whole Pareto frontier: if we consider two dimensions, signal (how capable are alumni of this program at doing AI safety research) and throughput (how many alumni can this program produce per year), then we get a Pareto frontier of programs. Programs generally optimise for signal (MATS, Astra, directly applying to AI safety-focused research labs) or for throughput (bootcamps, online courses):

I think it would be worth exploring a different point on the Pareto curve:

Research bounties

I’m imagining a publicly-accessible website where:

- Well-regarded researchers can submit research questions that they’d like to see written. This is already informally done via the “limitations” or “future work” sections in many papers.

- Companies or philanthropic organisations put up cash bounties on research questions of their choosing, with the cash going to whomever actually does the research. Any organisation/researcher can add a bounty to any research question. Researchers might put up a research question as well as a bounty, or might just put up the question, or might put up a bounty on another researcher’s question.

- Anyone can browse the open bounties and choose one to work on. This might involve the ability to “lock” a bounty, so that they can work for some fixed time period without stressing about someone else getting there first.

- “Claiming” the bounty would look like submitting a paper to an open-access preprint, along with reproduction steps for the data and graphs. When the original researcher approves of a paper, the bounty is paid out.

This mechanism effectively moves the bottleneck away from the number of people (researchers, research managers) and towards the amount of capital available (through research funding, charity organisations). It would serve the secondary benefit of incentivising “future work” to be more organised, making it easier to understand where the frontier of knowledge is.

This mechanism creates a market of open research questions, effectively communicating which questions are likely to be worth sinking several months of work into. Speaking from personal experience, a major reason for me not investigating some questions on my own is the danger that these ideas might be dead-ends for reasons that I can’t see. I believe a clear signal of value would be useful in this regards; a budding researcher is more likely to investigate a question if they can see that Anthropic has put a $10k bounty on it. Even if the bounty is not very large, it still provides more signal than a “future work” section.

Since these research question would have been proposed by a researcher and then financially backed by some organisation, successfully investigating these questions would be a very strong signal if you are applying to work for that researcher or an affiliated organisation. In this way, research bounties could function similarly to the AI safety fellowships in providing a high-value signal of competence at researching valuable question, hopefully leading to more people working full-time in AI safety. In addition, research bounties could be significantly more parallel than existing fellowships.

Open-source software already uses bounties, to great effect

Cyber security, the RL environments bounties from prime intellect, and tinygrad’s bounties are all good examples of using something more EMH-pilled to solve these sorts of distributed low-collaboration1 work. These bounty programs encourage more people to attempt to do the work, and then reward those who are effective. Additionally, the organising companies use these programs as a hiring funnel, sometimes requiring people to complete bounties in lieu of a more traditional interview process.

Research bounties are potentially a very scalable way to perform The Sort and find people from across the world who are able to make AI safety research breakthroughs. There are problems with research bounties, but there are problems with all options (fellowships, bootcamps, courses, etc) and the only valuable question to ask is whether the problems outweigh the benefits. I believe research bounties could fill a gap in the throughput-signal Pareto curve, and that this gap is worth filling.

Problem: verifying submissions

Once a research question has been asked, a bounty supplied, and a candidate has submitted a research paper that they claim would answer the question, we are left with the problem of verifying their claim. This is an intrinsically hard problem, one which peer review would solve. One answer would be to ask the researcher who originally posed the question to review the paper, but this is susceptible to low-quality spam answers. The reviewers could get some percentage of the bounty, but that could lead to perverse incentives.

Research bounties as prediction markets

Another option to verify submissions might be to pose the research bounty in the form of a prediction market. For example, if you had the open research question

Does more Foo imply more Bar?

you could put up a prediction market for

A paper showing that ‘more Foo implies more Bar’ gets more than 20 citations one year after publication.

To incentivise someone to answer the research question, an organisation could bet NO for some cash amount, and the creators of the research paper could bet YES shortly before making their paper public, thereby claiming the “bounty”. This would increase the feedback time between someone publishing a paper and getting paid, but it should significantly reduce the chance of someone getting paid for sub-par work (if the citation requirement is raised high enough).

Footnotes

-

By low-collaboration, I mean ~1 team/~1 person collaborating, as opposed to multiple teams or whole organisations collaborating together ↩