In an effort to write more and to think less, I’ll be publishing something every day during November. I’ve a bunch of drafts and partially-written posts which have merit but no polish, I’m hoping these short, low-polish, daily essays will give me an opportunity to say something rather than have the ideas decay slowly.

These mini-essays will be lower quality, poorly thought out, basically un-edited, and in general a lot more off-the-cuff thoughts. Imagine these a bit closer to Boyd’s stream-of-consciousness or late-night bar-thoughts than the other essays I write. But please let me know if any of them resonate!

Communicate the difference, not the absolute (30 November 2025)

When trying to express how unusual something is, focus on the difference, not the absolute. This is something that photos by default fail to do, because they only capture the instant in time and cannot effectively capture the difference. Videos are better, because you can capture the change over time which communicates the difference a bit better. Even better is to explicitly describe how things are the vast majority of the time and then show a photo of the unusual thing. Showing a photo of the majority of the time and then a photo of the unusual thing isn’t super effective, because the person you’re showing things will just see two photos and often underweight the rarity of the unusual thing

E.g. lots of birds at a bird feeder. 99% of the time there’s zero birds, sometimes there’s two or three. But six birds, boy oh boy that’s a lot of birds. But a photo of six birds at a bird feeder doesn’t communicate how rare it is to even see two birds, so the six birds look underwhelming.

This also explains why sunsets are boring. The impressiveness of a sunset is in how different it looks compared to the blue sky of the entire day, and a photo ignores the blueness of the day. Same for convincing people about the probability of x-risk: it’s a lot more convincing to talk about the rapid rate of progress than it is to show a demo of a kinda-janky robot doing boxing. The kinda-janky robot is incredibly impressive if you know that last year they could barely walk, but in absolute terms the kinda-janky robot is, well, kinda-janky.

Lawyers are uniquely well-placed to resist AI job automation (29 November 2025)

I believe that the legal profession is in a particularly unique place with regards to white-collar job automation due to artificial intelligence. Specifically, I wouldn’t be surprised if they are able to make the coordinated political and legal manoeuvres to ensure that their profession is somewhat protected from AI automation. Some points in favour of this position:

- The process of becoming a lawyer selects for smart people who are good at convincing others towards the lawyers opinion.

- Lawyers know the legal framework very well, and have connections within the legal system.

- Certain lawyers also know the political framework very well, and have connections within the political system.

- (delving a bit more into my opinions here) lawyers seem more likely to be see white-collar job automation coming and take steps to prevent it than many other professions. I would feel much more confident that I could convince a lawyer of the dangers of x-risk than similar attempts to convince a school teacher.

- Lawyers are well-paid and generally well-organised, so are in a good place to work collectively to solve problems faced by the entire profession.

I believe that as widely deployed AI becomes more competent at various tasks involved in white-collar jobs, there’ll be more pressure to enact laws that protect these professions from being completely automated away. The legal profession is in the interesting position of having large portions of the job susceptible to AI automation, while also being very involved at drafting and guiding laws that might prevent their jobs from being completely automated.

Politicians are probably even better placed to enact laws that prevent politicians from being automated, although I don’t believe politicians are as at-risk as lawyers. Lawyers are simultaneously at-risk for automation and very able to prevent their automation.

Whether the lawyers actually take action in this space is tricky to say, because there are so many factors that could prevent this: maybe white-collar automation takes longer than expected, maybe the politicians pass laws without clear involvement from large numbers of lawyers, maybe no laws get passed but the legal profession socially shuns anyone using more than an “acceptable level” of automation.

But if the legal profession were to take moves to prevent the automation of their own jobs, I’d be very surprised if they drafted an act titled something like “THE PROTECT LAWYERS AT ALL COSTS ACT”. I imagine the legal paperwork will protect several professions, with lawyers just one of them, but that lawyers will indeed be protected under this act. This is to say, I believe the legal profession to be fairly savvy, and if they do make moves to protect themselves against AI job automation, I doubt it’ll be obviously self-serving.

Legal code as computer code (28 November 2025)

|law |

I believe there’s a good argument for some parts of the legal code to be converted to computer code, such that answering certain (but not all) legal questions become basically free and basically instantaneous. (free as in beer).

Starting with why, I argue that legal fees and legal uncertainty create significant burden on many aspects of modern living. Being able to cheaply and quickly get answers to questions about the legality of certain situations would allow businesses to move faster and with more certainty about their situation. Implementing parts of the legal framework as computer code would allow for many of the powerful tools currently used for code review to be brought to bear against legal situations, such as collaborative pull-requests, specialised diff Is, automated version control, fuzz-testing (which might find loopholes in the legal framework), and automated testing of important cases.

There have been attempts (such as this for French tax law) which have had varying levels of success, and mostly horror stories at the lack of robust Software Engineering practices implemented.

I do not think the entirety of the legal code should be in computer code. I’ve spoken with enough lawyers about this idea to know this is not a good idea. There are aspects of the law that require a judgement call to be made. Most rental agreements will have something like:

The Tenant shall yield up the Premises in good repair and condition, reasonable wear and tear excepted.

meaning that the landlord will repair any damage that falls under “reasonable wear and tear”. While it’s maybe possible to define an algorithm that decides if something is “reasonable wear and tear” (especially with LLMs nowadays), I don’t see this as the core value-add of writing the legal framework in computer code. I see the core value-add as being able to inquire “there is nothing more than reasonable wear and tear, will I get my deposit back?“. While this question is trivial for many, legal contracts can quickly get more complicated than your run-of-the-mill rental agreement. In which case this ability to cheaply and quickly get truthful verdicts about the hypothetical effects of your actions on a contract is extremely powerful.

Discussions with lawyers have also made it apparent that making modifications to a complicated legal document is a horrifying challenge compared to modern software engineering standards, and git-like version control or diffing support is basically non-existent. Additionally, there is a large amount of the legal framework that is (intentionally or unintentionally) vague and this ambiguity is only cleared up when an actual case is brought before a judge and a ruling is passed. This is what software developers would call “testing in production”, and is generally considered a very bad idea. Once the legal system makes a ruling, that ruling becomes law. The existence of case law makes it very difficult to fully understand the implications of the law as written, or to convert the legal code into computer code, because reading all the laws in a country is insufficient. One must also read and interpret every ruling ever made by any judge in the country.

This above paragraph was terrifying to write, and I’d love to be proven wrong about the claims there. But as far as I know, they’re correct. We regularly “test in production”, with real people’s lives on the line.

I think that if we could pull this off, the benefits would outweigh the costs. Actually pulling it off would be a gargantuan task, however.

Are narrative emotions passed by value, or by reference? (27 November 2025)

Something that I’ve been having doubts about, is whether it’s possible to truly feel an emotion invoked by a compelling story, if you’ve not yet lived a similar experience to that story. My parents are both still alive, so when I read a moving book about a child losing a parent, do I really feel the emotion?

This is trivially true in some less-than-fully-meaningful way. I believe most people would agree that you would feel more moved by a story about the death of a parent after having lost your own. To argue the counter-claim --- that you could experience something like your parent passing away and not feel more moved by something that’s making you remember the event --- seems unlikely.

So this idea gets extended slightly, and we’re in a weird place: is every story that makes you feel something “just” referencing a previous similar experience you’ve had? Does a heartbreak romance resonate with you more once you’ve had your heart broken? This feels somewhat true to me; I’m not sure that I actually understand what it’s like to watch a loved one be lost to cancer or to have a child become addicted to a life-destroying drug. I’m not sure that, watching a film or reading a book about this, I actually feel moved by these events, beyond compassion for the characters and partial pattern matching these events onto those semi-similar events of my own life.

If this were true, then ~all fiction that is emotionally moving is really a reference to the tragedies of your own life, and when the characters undergo their torment and you feel their heartbreak, it is really a re-living of your own sad days.

Books cover a larger idea-space than movies (26 November 2025)

Read on LessWrong |memeticsideasoverton-windowlesswrong

I’m hoping that multi-modal embedding models (which convert videos, images, and text into points in a high-dimensional space such that a video of a dog, a photo of a dog, and text describing a dog all end up close together) will allow this statement to be formalised cheaply in the near future.

If you consider the “range” of ideas that are conveyed in books, and the range of ideas that are conveyed in movies, I certainly have the intuition that books seem to be much broader/weirder/different in the ideas they describe when compared to movies. Movies, by comparison, seem muted and distinctly more “normal”.

I believe this to be due to how these two media come to be: movies are enormously expensive, and require the creative input of dozens to ~100s of people (writers, actors, producers, sound & music, lighting, video, VFX, set design, the list goes on). If a screenwriter has a complicated idea and wants it to appear in a film, each of these people has to understand (and importantly, care) about this idea for it to actually arrive on-screen in its original form. This puts an upper bound on how “weird” an idea can be for it to be on the big screen.

I’m less informed about the production of books, but I’m struggling to imagine more than 30 people who could have an impact on the creative aspects of a book. As an upper bound, maybe you have multiple authors, multiple editors, and several people from the publisher. But as a lower bound, I imagine you could write a book with creative input from just the author and the editor. If an author has a unusual idea they want to convey, they just have to make sure their one editor doesn’t dilute the core paragraphs too much, and this idea can then go straight into the reader’s noggin.

You might quibble with my “100s of people” characterisation for movies, but that’s okay because this exact number doesn’t matter, it just matters that most movies involve more people than most books. Because the distinction isn’t really movies-vs-books, it’s about the number of people involved: The more people involved, the trickier it is to get slippery ideas through them all, and so the more “normal” your ideas have to become.

You can see this by looking at low-headcount “movies” (YouTube videos, indie films, short films) which tend to be more out-there and weird, and also by looking at high-headcount “books” (pop-sci, magazines, newspapers) which tend to have more in-distribution ideas. You can even expand this to other creative media such as podcasts, theatre, poetry.

Creative media are ideal for doing this sort of headcount-vs-overton-window analysis, because there’s typically very little that fundamentally constrains what the message can be in creative media.

The headcount-overton-window tradeoff also applies to startups, organisations, political campaigns, public movements, although these have more constraints than creative media, such as profitability, existing in the physical world, convincing investors. But there’s a reason why “donate to save this puppy” is an easier pitch than “donate to save these shrimp”.

Discussing memetics is always tricky, but I do believe this tradeoff is real, and that it effects the objects we see in the world. We can draw informative conclusions from this tradeoff: to find unique ideas, you must consume content that required very few people’s approval in order to exist (e.g. blogs, preprints, off-the-cuff discussions with smart people). To produce unique ideas, you will be fighting an uphill battle if you subject that idea to other’s opinions. Sometimes this battle is worthwhile; I said the ideas would be unique, not good. But every novel idea you introduce is something that needs to fight for space in someone’s mind, and you’ll need to convince them not to project your idea onto their existing map of the world. Every introduction is a chance for failure of communication (which may go unnoticed by you). But also, every introduction is a chance for someone to cull your bad ideas.

So when you feel in a rut, and lacking interesting thoughts, consider the media you consume. Are you sampling from the same distribution as everyone else? By how much has the media you consume been filtered (either anthropically or algorithmically)? Books, for me, are second to none for novel ideas, and I look forward to being able to demonstrate this empirically.

HTTP 402: how the internet could have been ad-free (25 November 2025)

Read on LessWrong |http402economicspaymentslesswrong

Crypto could have been really good, before it became a synonym for scams and money laundering schemes. Having a native currency for the internet could have (and I guess, still might) enable many interesting innovations, such as allowing for significantly cheaper and smaller transactions. The high friction and financial cost of doing small (<$5) transactions is, I argue, a reason why subscriptions are the dominant form of payment on the internet nowadays, instead of once-off payments. Many internet-based products have very small unit-prices (e.g. one YouTube video, one essay, one search result), and because it’s infeasible to charge for these individually, we end up with subscriptions and adverts.

I’m aware that it’s much nicer for a business’s cash flow to have monthly subscribers that semi-reliably make payments. It’s terribly inconvenient to pay for fixed operating expenses (payroll, rent, etc) with unpredictable revenue. But what’s the cost to the business of these niceties? I’d certainly pay for more internet services if it were easier to do once-off payments. The existence (and success) of micro-transactions lends evidence to how many small payments can still be profitable as a business model. I’m not 100% convinced that many small once-off payments would be more profitable than subscriptions, but I’m fairly certain.

Imagine this scenario:

- A friend sends you an article by the New York Times

- You click the link, and get bombarded with a subscription pop-up

Today, you’d either already have a subscription and log in, or you bounce from the article. Occasionally, you might sign up for a subscription. But in Boyd’s alternate timeline with easy & cheap transactions:

- the NYT website sends an

HTTP 402: payment requiredresponse to your browser - This response tells your browser that viewing this article (and this article alone) will cost you $1.

- You like the NYT, and have allowed your browser to auto-pay for any

single webpage from the

nytimes.comdomain, so long as it’s less than $1.50 - Your browser makes a small payment to the NYT, and replies to the HTTP402 response.

- The NYT website, seeing that you’ve paid for the article, responds with the actual content. Because you’ve paid for it, there are no adverts on the page.

- Critically, all this can be done automatically, without you having to do anything besides set a limit for the domains you trust.

This works out quite well for all involved. The readers don’t get bombarded with popups asking for subscriptions, and also get to read the thing they wanted to read. The journalists get paid. The NYT gets incredibly detailed insight into how much people are willing to pay for individual articles. More precisely, this mechanism has created a very precise market for individual articles, ideally leading to a more efficient allocation of resources.

This of course has security risks, since an attacker can now transfer funds via a well-placed HTTP response or browser exploit. I’m not sure about a good solution to this. But web servers are incentivised by their reputation to be secure (not that this is fool-proof). Web browsers could ship with very low cash-transfer limits by default, and require a password before any payment is made.

Beyond these significant problems, I would personally love to pay some once-off price for ~every article that I get sent, but subscribing to every news platform, substack, streaming service, etc is too much for me.

~everything is a random search, just over different domains (24 November 2025)

Sometimes I wonder how much of modern scientific advancements are really just random search in disguise. Given my framing above (where everything is random search), this question doesn’t really make sense. But from a more day-to-day understanding, I’m not sure how to properly attribute an innovation to someone being incredibly smart and seeing the gap that nobody else could, versus taking a more holistic view and thinking that it’s inevitable that someone would eventually attempt the innovation in question.

It’s not like we get repeated randomised trials at discovering something for the first time. If you have thousands of people working full time on a problem for years, it’s not a forgone conclusion that any progress will be made (some problems are just that hard), but scientific progress is not a once-in-a-decade phenomenon.

If you cannot be good, at least be bad correctly (23 November 2025)

Read on LessWrong |lesswrongasymmetric-penaltieserr-correctly

It’s hard to be correct, especially if you want to be correct at something that’s non-trivial. And as you attempt trickier and trickier things, you become less and less likely to be correct, with no clear way to improve your chances. Despite this, it’s often possible to bias your attempts such that if you fail, you’ll fail in a way that’s preferable to you for whatever reason.

As a practical example, consider a robot trying to crack an egg. The robot has to exert just enough force to break the egg. This (for a sufficiently dumb robot) is a hard thing to do. But importantly, the failure modes are completely different depending on whether the robot uses too much force or too little: too much force will break the egg and likely splatter the yolk & white all over the kitchen, too little force will just not break the egg. In this scenario it’s clearly better to use too little force rather than too much force, so the robot should start with a lower-estimate of the force required to break the egg, and gradually increase the force until the egg cracks nicely.

This also appears in non-physical contexts. This idea is already prevalent in safety related discussions: it’s usually far worse to underestimate a risk than it is to overestimate a risk (e.g. the risk of a novel pathogen, the risk of AI capabilities, the risk of infohazards).

Looking at more day-to-day scenarios, students regularly consider whether it’s worth voicing their uncertainty “I don’t understand equation 3” or just keeping quiet about it and trying to figure out the uncertainty later. But I’d argue that in these cases it’s worthwhile having a bias towards asking rather than not asking, because in the long-run this will lead to you learning more, faster.

Salary negotiation is another example, in which you have uncertainty about

exactly what amount your potential employer would be happy to pay you, but in

the long-run it’ll serve you well to overestimate rather than underestimate.

Also, you should really read patio11’s Salary

Negotiation essay if

you or a friend is going through a salary negotiation.

You see similar asymmetric penalties with reaching out to people who you don’t know, asking for introductions, or otherwise trying to get to know new people who might be able to help you. It’s hard to know what the “right” amount of cold emails to send is, but I’d certainly rather be accused of sending too many than feel the problems of having sent too few.

This idea is a slippery one, but I’ve found that it applies to nearly all hard decisions in which I don’t know the right amount of something to do. While I can’t figure out the precise amount, often I have strong preferences about doing too much or too little, and this makes the precise amount matter less. I give my best guess, update somewhat towards the direction I’d prefer to fail, and then commit to the decision.

Where is the $100k iPhone? (21 & 22 November 2025)

100k-iphoneeconomicsconstraintsbillionaires

Note: this idea is more complex than some other ones, so I’ve written it over two days

I’m not quite sure how unequal the world used to be, but I’m fairly certain the world is more equal (in terms of financial means) than the world was, say, in the 1600s.

If you’re ultra-wealthy ($100M+), then there are many things that wealth affords you to buy that’s out of reach for middle-class American consumers, like yachts, personal assistants, private jets, personal assistants, multiple homes, etc. You can frame these things in terms of the problems they solve e.g. private jets solve the problem of travelling long distances, multiple homes solves the “problem” of wanting to go on vacation more often. Most of these problems are also present in middle-class Americans, it’s just that the middle-class American has to solve them differently. Instead of a private jet, they travel using commercial airlines. Instead of multiple homes, they go on vacation and stay in a hotel or similar.

Most goods or services seem to be available at wide range of prices, with the higher end being around 2 or maybe 3 orders-of-magnitude greater than the lower end. For example:

- Food: Higher end would look like full-time personal chef and regular fine-dining, lower end would look like grocery store pre-packaged meals and cheap fast-food.

- Short-distance travel: Higher end would look like a full-time chauffeur in a custom Bentley, lower end would be public transport or an old car.

- Long-distance travel: Higher end would frequent private jet flights, lower end would be infrequent commercial airline travel

- Time-telling: ~$10 Casio through to a ~$100k Rolex

- Education: free public school vs ~$50k/year elite schools + private tuition

- Politics: Democratic voting is free, but if you’re willing to spend $100k+, you too can lobby for areas of your choosing or sponsor political candidates.

- Healthcare: regulation makes this less clear than other cases, but you and I certainly can’t afford to fund medtech startups looking to cure aging.

I have low confidence that the difference is precisely 100x to 1000x, but I’m very certain that it’s a large multiple, rather than 1.1x to 2x.

But you then get some products which, weirdly, do not exhibit this behaviour. Even the wealthiest man in the world will likely use the same iPhone, play the same video games, read the same books, and watch the same movies as a middle-class American. What gives? What is the underlying factor that means some goods and services have 1000x range in value, and others have basically no difference?

Books and movies might be a slight outlier here: centi-millionaires absolutely can pay or sponsor creative professionals to produce work that they specifically wish to exist. This might be explicit (contracting a director to make a specific film), but more likely this is implicit (funding a film studio, sponsoring an artwork, organising meet-and-greets with powerful donors).

But Apple seems surprisingly resilient to creating a $100k iPhone. There are several possible reasons:

- Innovation-constrained: the modern iPhone is just at the limit of what’s technically feasible, and Apple wouldn’t know what to do with the money if you gave it to them. You could pay every Apple engineer and designer 100x their current salary, and they wouldn’t be able to innovate[^8] more than they currently are because they’re already at the limit of human innovation.

- Economics-constrained: producing large numbers of $1000 iPhones is just much more profitable than fewer numbers of $100k iPhones, so there’s no incentive to make a more expensive iPhone.

Option 1 seems a little fishy to me. I’m not sure, but I doubt there’s nothing Apple could do to put more high-end features in a $5k iPhone. $100k does start to push the limits, but $1k seems low considering the frequent critique of iPhones.

Option 2 also doesn’t quite sit right with me. It seems okay on its own, but I don’t see why iPhones would have this dynamic but not watches, furniture, cars, etc.

One third option that I think is closer to the money:

- Things improve too frequently, so nobody’s willing to drop $100k on a hyper-specialised luxury iPhone that’ll be out-of-date in a year. If there’s a technical innovation in batteries or screens or cameras, then next year’s consumer iPhone will have the brilliant innovation but your luxury iPhone won’t.

Consumer technology experiences game-changing innovations much more regularly than, say, cars or furniture or housing. So under option 3 we’d expect most goods or services that have a very small financial range to be either tech products or things that are undergoing rapid innovation and change.

This seems to hold up: laptops, smartphones, internet services (like YouTube, Netflix, Gmail, etc), Starlink, all have a very small financial range, some of them you can’t buy a more expensive variant even if you wanted to.

Looking at the other side of the coin, gas-powered cars have been stagnant for several decades. There have been improvements in comfort, efficiency, and safety, but I’d argue that these improvements stem more from increased demand for these features rather than previous inability to innovate in these features.

I suspect there’s something deeper here, uses the range of prices you can pay for a good or service as a measurement for the amount of innovation the market expects the service to undergo. This would predict that areas where the market predicts frequent game-changing innovation would have a very narrow range of prices, but areas which the market considers stagnant to have a very wide range of prices. But a full analysis will have to wait for the full post

Non-human non-machine intelligence (20 November 2025)

Epistemic status: highly uncertain, probably wrong.

I have a slight intuition that we have not really put much effort into discovering how smart non-human animals can be. Police dogs are probably the best example of animals where institutional effort and significant funding has been applied to maximising animal intelligence.

But I feel there’s scope for something more ambitious, and that there could be enough upside to motivate some capital. I have octopuses in mind, but I imagine that other animals might also be worth studying. A selective breeding program[^7] targeting intelligence and suitability for study would be interesting, but likely difficult for octopuses.

But why do this? I’m uncertain, but non-human intelligence seems like such an alien prospect that it should be worth exploring. Basically everything we know about the world is viewed through the lens of our own intelligence. I feel certain that if we knew more about non-human intelligence, we would find something interesting.

As a start, it would be interesting to develop real-world contraptions that automatically reward behaviour. For example, a box that rewards crows with some food if they put some litter in a container, or something similar to reward octopuses for finding and disposing of ocean trash. I think it’s important for this to be automated, because the chance of success is so incredibly tiny that these would have to be operating 24/7 and deployed en mass.

AI art shows that AI won’t just create new, better jobs (19 November 2025)

ai-arteconomicsgradual-disempowermentartificial-intelligence

I semi-regularly hear the argument that:

AI might remove some jobs, but the automation will enable new, better jobs that we don’t have the words for yet. See how computers and spreadsheet software and CAD software have all enabled people to do new jobs

I’m empathetic to this viewpoint, although I’m fairly certain it’s wrong. Believing that “AI will be different” smells a lot like “trust me bro” if you haven’t been following AI progress for a few years.

An illustrative example for why I think AI will not simply produce more jobs than it removes, is the digital artists. There was a brief period of a few months where AI art would regularly mess up the fingers, and it wasn’t that good, and you could still tell the difference if you looked closely. We’ve since passed this point, and current AI art is indistinguishable from anything a human can make.

So the role of digital artist has been completely automated by AI. Have the ex-artists found better paying jobs? No, they haven’t. Artists were automated away because AI didn’t automate a specific task or a specific process, it automated the entire job.

I’m pessimistic about AI allowing us to automate the boring things and allow us to do more interesting, better paid jobs, because the explicit goal of most frontier AI companies is the automation of human cognition. Anything that a human can think about, they aim to build a machine that can think about.

So it’s unclear to me what these “more interesting” jobs are, where humans still have a competitive advantage over the AIs that can do any white-collar work that a human can do. A few years ago we might have thought this would be “creative”, “left-brained” tasks that computers are bad at. But digital artists are the epitome of creative work, and computers are doing their job just fine. I don’t see what employment will be competitive for humans to do, since it definitionally needs to be something that can’t be done by human-equivalent cognition.

The only answer I can see to this is to keep the future human, and to outright forbid the complete automation of human labour. But this also feels like how we artificially hold back humanity from solving some of the hardest problems out there, such as cancer, ageing, global coordination, etc. I’m personally bullish on artificial narrow intelligence (such as AlphaFold, self-driving cars, using computer-vision to interpret medical scans, etc) as a means for empowering humanity through AI without succumbing to the problems of mass-automation.

We already have super-human AI persuasion machines (18 November 2025)

doomscrollingsocial-mediapersuasionartificial-intelligence

Sometimes, I hear an argument against ASI that goes something like:

Sure, it might be really good at programming or mathematics, but that won’t get anything real done in the world, and I don’t see how it could have any effect on people. To do something, you have to have people enacting change in the world

To steel man this perspective, basically all the reported leaps and bounds in AI are about improved programming or mathematics abilities, and basically nothing is about their effect on people.

But there is an easy existence proof that shows this will not remain the case for long: social media algorithms are built from exactly the same foundations as modern AI, and often the same researchers who got millions addicted to their phones are now working on these AIs. To emphasise this point, I’ll refer to social media algorithms as “doomscroll-AIs” and AIs like ChatGPT or Claude as “chatbot-AIs”

The main difference between doomscroll-AIs and chatbot-AIs is the goal that the researchers had while building them. Doomscroll-AIs are built to maximise ad revenue, which usually means keeping users on the platform for as long as possible. The first example of an algorithmically-curated social media feed is Facebook’s first algorithm called EdgeRank in 2009. Doomscroll-AIs have been under over a decade of optimisation pressure to become better and better, while chatbot-AIs have only been broadly deployed for less than 5 years.

I’m not certain that chatbot-AIs will become as profit-driven and generally-unhealthy as current doomscroll-AIs, mostly because I think there might be more money from automating white-collar labour (which has it’s own problems) than from ad revenue, which would lead to the tech giants focussing on optimising for white-collar employability rather than eyeballs.

If you’re still unconvinced, have a look at this

paper

which was eventually retracted due to

controversy (despite

being approved by the University of Zurich’s ethics board). The study got a

chatbot-AI to make comments on r/changemyview, a subreddit where people post

their views, and other people comment attempting to convince the original

poster why they are wrong. Nobody realised that the comments were being made by

an AI, and the chatbot-AI was better than 99% of other users on the site (and

better than 98% of the most persuasive human experts on the forum).

I am very certain that current chatbot-AIs could become as (if not more) engaging as doomscroll-AIs: existing doomscroll-AIs show that it’s possible for an algorithm to learn your preferences and interests better than any human (arguably, even better than your significant other). And chatbot-AIs are significantly better at understanding how people work and interpreting images/videos than existing doomscroll-AIs. If the power of chatbot-AIs gets applied to the goal of doomscroll-AIs, I’m very confident that they’ll be able to achieve super-human manipulation. Which is terrifying.

AI usage disclaimer: Claude 4.5 Sonnet found Facebook’s EdgeRank to be the first social media algorithm feed

Sign language as a generally-useful means of communication - even if you have good hearing (17 November 2025)

Read on Less Wrong | #sign-languagecommunicationpracticallesswrong

Sign languages[^6] are interesting to me because they use a fundamentally different medium of communication: sight instead of sound. Generally, sign languages are ignored by those who can speak and who don’t have to communicate with deaf people. But I believe they have utility beyond communicating with deaf people because it’s common to be in a place where you want to communicate but it’s either too loud or too far to do so via speech. Some examples:

- In a coworking space or library where the room is silent, you could use sign language to ask a question to someone nearby, or to ask a question across the room without disturbing anyone

- In a meeting or during a talk you could similarly ask & answer questions without interrupting the meeting. This might be particularly useful to check in with peers in real time, as the meeting is happening

- high-end service workers or organisers could use a sign language to convey logistical information (“we’re running out of X”, “is the next speaker ready?”, etc) without disrupting the event that they’re facilitating

- Across a large distances such as a football field or from atop tall buildings, you could use a sign language to communicate without having to walk within earshot (although admittedly the clarity of the signs will degrade with distance)

- In a bar, you could use sign language to tell your order to the bartender without having to shout above the music

Beyond sign languages utility in isolation, sign language also has utility in that it can provide redundancy to the spoken word. This is useful when communicating important information in noisy environments, such as the size of a bill at a loud restaurant, or possibly just for emphasis of an important point.

As far as I see, the main downside to learning a sign language is the lack of people to speak with! This seems like a fun hobby for a couple or friend group to pick up, since I imagine there’d be benefit if the people you see most often all speak a sign language together. I also imagine that I’m missing some benefits that only become apparent after actually using sign language as an auxiliary means of communication for some time.

The burden of proof should be on frontier AI labs (16 November 2025)

burden-of-proofartificial-intelligencepolicy

There’s a simple answer to AI art being created from artwork that was not given with permission, which is to set a legal precedent that any art created before 2023 (or whenever) was created without the expectation of AI art generation technology, and that even if it is permissively licensed, this license should not in fact cover usage for training an AI.

”Just be a better parent” is not good advice (15 November 2025)

parentinglong-term-planningepistemics

Teaching children is tricky because they pattern match all the time, not just when you’re on your best behaviour. While I’m not a parent, it seems that much advice about parenting is about the parent aspirationally being a better person as a role model for the child. Even things such as explaining why stealing is bad or why vegetables are good, I’m somewhat doubtful about how effective they are when compared to the child pattern matching off of their parent for literally every waking hour of the child’s life.

To the degree that most people are good people, most children have good role models. But I’m unconvinced that you can teach your child to have a habit of eating well if you yourself do not have a habit of eating well. You might strongly remember the lesson you gave your child about the importance of healthy eating, but if your child sees you ordering take-outs every Friday when you’re too tired or stressed to cook something healthier, I don’t think the child is going to ignore what they’re seeing in favour of what you’re saying.

A counter to this is how parents become better people when they have their children.

I’m unsure about whether you can choose to not pass on your bad habits to your child, because 20 years is a very long time to hide those bad habits from someone who’s living with you, day in and day out. If you smoke every day and tell your child every time that they should never smoke, the child is going to eventually try a cigarette.

If you seriously want to not pass on your bad habits to your children, I think there’s only two ways to go about it: either fix those bad habits in yourself, or find a partner who does not have those bad habits (and ideally whom encourages you to be your best self).

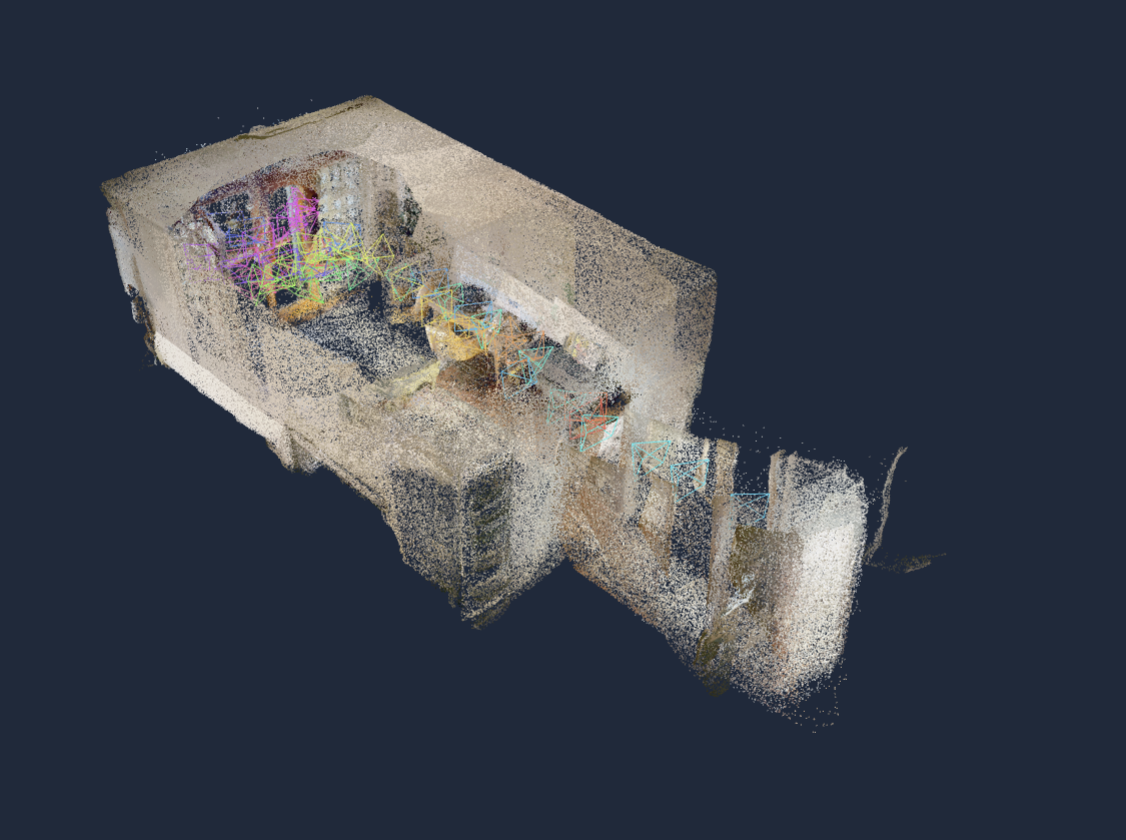

You should splat your home (14 November 2025)

Digitally storing an area for later walking around it has come so far:

It’s now pretty quick, trivial (and free) to create point clouds or splats from a handful of photos. I used Depth Anything 3, but I’m sure there are others.

If you’re going to be moving soon, or just want to capture the moment, taking the time to capture enough images for a decent Gaussian splat will likely be similar to cryogenically freezing yourself in the hopes of future technology resurrecting you. Except it’s a lot more likely that there’ll be better-fidelity VR and SLAM in the future than resurrection.

Regardless, taking a lot of very detailed high-fidelity high-coverage photos of areas that you care about will likely be very treasured by your future self when you can no longer visit those areas. The point clouds aren’t great today, but this is the worst they’ll ever be.

Bad things should feel bad (13 November 2025)

If something is a bad situation, you shouldn’t take steps to make it feel less bad (and therefore reduce the chance you’ll actually fix the situation. The feeling bad is correct, it’s feedback to your brain to encourage you to fix the thing.

We live in the luckiest timeline (12 November 2025)

Read on LessWrong |timelinesexistential-risknuclear-riskbio-risk

When considering existential risk, there’s a particular instance of survivorship bias that seems ever-present and which (in my opinion) impacts how x-risk debates tend to go.

We do not exist in the world that got obliterated during the cold war. We do not exist in the world that got wiped out by COVID. We can draw basically zero insight about the probability of existential risks, because we’ll only ever be alive in the universes where we survived a risk.

This has some significant effects: we can’t really say how effective our governments are at handling existential-level disasters. To some degree, it’s inevitable that we survived the Cuban Missile Crisis, that the Nazis didn’t build & launch a nuclear bomb, that Stanislav Petrov waited for more evidence. I’m going to paste the items from Wikipedia’s list of nuclear close calls, just to stress this point a bit:

- 1950–1953: Korean War

- 1954: First Indochina War

- 1956: Suez Crisis

- 1957: US accidental bomb drop in New Mexico

- 1958: Second Taiwan Strait Crisis

- 1958: US accidental bomb drop in Savannah, Georgia

- 1960: US false alarm from moonrise

- 1961: US false alarm from communications failure

- 1961: US strategic bomber crash in California

- 1961: US strategic bomber crash in North Carolina

- 1962: Cuban Missile Crisis

- 1962: Soviet averted launch of nuclear torpedo

- 1962: Soviet nuclear weapons in Cuba

- 1962: US false alarm at interceptor airbase

- 1962: US loss of ICBM launch authority

- 1962: US mistaken order during Cuban Missile Crisis

- 1962: US scramble of interceptors

- 1964: US strategic bomber crash in Maryland

- 1965: US attack aircraft falling off carrier

- 1965: US false alarm from blackout computer errors

- 1966: French false alarm from weather (likely)

- 1966: US strategic bomber crash in Spain

- 1967: US false alarm from weather

- 1968: US strategic bomber crash in Greenland

- 1968–1969: Vietnam War

- 1969: DPRK shootdown of US EWAC aircraft

- 1969: Sino-Soviet conflict

- 1973: Yom Kippur War

- 1979: US false alarm from computer training scenario

- 1980: Explosion at US missile silo

- 1980: US false alarm from Soviet missile exercise

- 1983: Able Archer 83 NATO exercise

- 1983: Soviet false alarm from weather (likely)

- 1991: Coalition nuclear weapons

- 1991: Gulf War

- 1991: Israeli nuclear weapons

- 1991: Tornado at US strategic bomber airbase

- 1995: Russian false alarm from Norwegian research rocket

- 2007: Improper transport of US nuclear weapons

- 2017–2018: North Korea crisis

- 2019 India-Pakistan conflict

- 2022–present: Russian invasion of Ukraine

That’s… a lot of close calls.

And sure, very few of them would likely have been existential-level threats. But the list of laboratory biosecurity incidents is hardly short either:

- 1903 (Burkholderia mallei): Lab worker infected with glanders during guinea pig autopsy

- 1932 (B virus): Researcher died after monkey bite; virus named after victim Brebner

- 1943-04-27 (Scrub typhus): Dora Lush died from accidental needle prick while developing vaccine

- 1960–1993 (Foot-and-mouth disease): 13+ accidental releases from European labs causing outbreaks

- 1966 (Smallpox): Outbreak began with photographer at Birmingham Medical School

- 1967 (Marburg virus): 31 infected (7 died) after exposure to imported African green monkeys

- 1969 (Lassa fever): Two scientists infected, one died in lab accident

- 1971-07-30 (Smallpox): Soviet bioweapons test caused 10 infections, 3 deaths

- 1972-03 (Smallpox): Lab assistant infected 4 others at London School of Hygiene

- 1963–1977 (Various viruses): Multiple infections at Ibadan Virus Research Laboratory

- 1976 (Ebola): Accidental needle stick caused lab infection in UK

- 1977–1979 (H1N1 influenza): Possible lab escape of 1950s virus in Soviet Union/China

- 1978-08-11 (Smallpox): Janet Parker died, last recorded smallpox death from lab exposure

- 1978 (Foot-and-mouth disease): Released to animals outside Plum Island center

- 1979-04-02 (Anthrax): Sverdlovsk leak killed ~100 from Soviet military facility

- 1988 (Marburg virus): Researcher Ustinov died after accidental syringe prick

- 1990 (Marburg virus): Lab accident in Koltsovo killed one worker

- 1994 (Sabia Virus): Centrifuge accident at BSL3 caused infection

- 2001 (Anthrax): Mailed anthrax letters killed 5, infected 17; traced to researcher’s lab

- 2002 (Anthrax): Fort Detrick containment breach

- 2002 (West Nile virus): Two infections through dermal punctures

- 2002 (Arthroderma benhamiae): Lab incident in Japan

- 2003-08 (SARS): Student infected during lab renovations in Singapore

- 2003-12 (SARS): Scientist infected due to laboratory misconduct in Taiwan

- 2004-04 (SARS): Two researchers infected in Beijing, spread to ~6 others

- 2004-05-05 (Ebola): Russian researcher died after accidental needle prick

- 2004 (Foot-and-mouth disease): Two outbreaks at Plum Island

- 2004 (Tuberculosis): Three staff infected while developing vaccine

- 2005 (H2N2 influenza): Pandemic strain sent to 5,000+ labs in testing kits

- 2005–2015 (Anthrax): Army facility shipped live anthrax 74+ times to dozens of labs

- 2007-07 (Foot-and-mouth disease): UK lab leak via broken pipes infected farms, 2,000+ animals culled

- 2006 (Brucella): Lab infection at Texas A&M

- 2006 (Q fever): Lab infection at Texas A&M

- 2009-03-12 (Ebola): German researcher infected in lab accident

- 2009-09-13 (Yersinia pestis): Malcolm Casadaban died from exposure to plague strain

- 2010 (Classical swine fever): Two animals infected, then euthanized

- 2010 (Cowpox): First US lab-acquired human cowpox from cross-contamination

- 2011 (Dengue): Scientist infected through mosquito bite in Australian lab

- 2012 (Anthrax): UK lab sent live anthrax samples by mistake

- 2012-04-28 (Neisseria meningitidis): Richard Din died during vaccine research

- 2013 (H5N1 influenza): Researcher punctured hand with needle at Milwaukee lab

- 2014 (H1N1 influenza): Eight mice possibly infected with SARS/H1N1 escaped containment

- 2014-03-12 (H5N1 influenza): CDC accidentally shipped H5N1-contaminated vials

- 2014-06-05 (Anthrax): 75 CDC personnel exposed to viable anthrax

- 2014-07-01 (Smallpox): Six vials of viable 1950s smallpox discovered at NIH

- 2014 (Burkholderia pseudomallei): Bacteria escaped BSL-3 lab, infected monkeys

- 2014 (Ebola): Senegalese epidemiologist infected at Sierra Leone BSL-4 lab

- 2014 (Dengue): Lab worker infected through needlestick injury in South Korea

- 2016 (Zika virus): Researcher infected in lab accident at University of Pittsburgh

- 2016 (Nocardia testacea): 30 CSIRO staff exposed to toxic bacteria in Canberra

- 2016–2017 (Brucella): Hospital cleaning staff infected in Nanchang, China

- 2018 (Ebola): Hungarian lab worker exposed but asymptomatic

- 2019-09-17 (Unknown): Gas explosion at Vector lab in Russia, one worker burned

- 2019 (Prions): Émilie Jaumain died from vCJD 10 years after lab accident

- 2019 (Brucella): 65 workers infected at Lanzhou institute; 10,000+ residents affected

- 2021 (SARS-CoV-2): Taiwan lab worker contracted COVID Delta variant from facility

- 2022 (Polio): Employee infected with wild poliovirus type 3 at Dutch vaccine facility

I’m making you scroll through all these things on purpose. Saying “57 lab leaks and 42 nuclear close calls” just leads to scope insensitivity about the dangers involved here. Go back and read at least two random points from the lists above. There’s some “fun” ones, like “UK lab sent live anthrax samples by mistake”.

Not every one of these is a humanity-ending event. But there is a survivorship bias at play here, and this should impact our assessment of the risks involved. It’s very easy to point towards nuclear disarmament treaties and our current precautions around bio-risks as models for how to think about AI x-risk. And I think these are great. Or at least, they’re the best we’ve got. They definitely provide some non-zero amount of risk mitigation.

But we are fundamentally unable to gauge the probability of existential risk, because the world looks look the same whether humanity had gotten 1-in-a-hundred lucky or 1-in-a-trillion lucky.

None of this should really be an update. Existential risks are absolute and forever, basically every action is worth taking in order to reduce existential risks. But in case there’s anyone reading this who thinks x-risk maybe isn’t all that bad, this one’s for you.

AI usage disclaimer: Claude 4.5 Sonnet helped reformat and summarise the lab-leak list which I skimmed for correctness.

On the value of legible skills (11 November 2025)

legibilityseeing-like-a-stateskill-development

Having skills isn’t valuable, having skills legible to the market is valuable. It really doesn’t matter how good you are, unless your potential mentors/employers/supervisors can distinguish you from the other thousand people who applied to that position.

Even if you believe your skills speak for themselves in the output they produce (code projects, high scores, secured deals, etc), these projects “speaking for themselves” is just a sub-optimal way of making your skills legible to the world; sub-optimal in the fact that they communicate your skills to fewer people than a technical write-up would, because fewer people read 1000+ line code bases than 1000-word blog posts.

There’s another way in which this phenomenon makes itself visible onto the world. It’s possible that you can spend a year “getting better at your craft”: doing impressive projects, writing descriptions of what you’ve already done, analysing exist code. But to some degree, you can make yourself more viable in the global market by focussing on legible projects over illegible projects. It’s entirely possible that you don’t intrinsically become more employable over some period of time, but that your skills do become more legible, which in turn leads to you becoming more employable.

I don’t think that this needs to have an impact on the projects you pursue nor

the technical decisions you make in those projects. But a well-laid our

README.md with some pictures can go a long way to making your skills more

legible. Even an AI-written README.md is, in my opinion, better than

literally nothing at all (although not significantly better, mind you).

In praise of process (10 November 2025)

You can create things or you can create processes which manipulate things. The creation of processes is often overlooked or ignored, but anyone who’s stood at a government office being told “Sorry the system won’t let me do that” knows the power that processes can have.

A well-crafted process guides people in how they go about their work or their lives, and almost always silently avoids pitfalls and mistakes. A well-designed airport can be seen as a people-moving process, one which maximises throughput and minimises lost travellers. When a process becomes distributed — it’s full operation requiring the actions of multiple people — it will sometimes outlive it’s creator, to the degree that no individual person is aware of the full process nor the impact of every minutia of their role in it. This leads to processes which are long-lasting, for better or for worse. But critically, it also leads to processes which are largely independent of the people sustaining them. If a process has no single team or person ensuring it’s survival (and assuming it does in fact survive) then that process can continue to serve the goals of it’s creators even through the failures of those who carry out the process. A well-made process has contingencies for (the inevitable and forgiveable) human failures, in such a way that does not blame the human involved.

During failure or after a crisis, it’s easy to blame people. But people come and go: politicians leave office, employees get promoted or fired. If you blame the people, and chastise the individuals until you’re absolutely super-duper-certain they’ll never do such a thing again, you’re leaving yourself open to literally everyone who comes after them making the same mistake. But if you blame (and later fix) the process, then you’ve ensured that no matter who’s in charge, the process will shield against the worst outcomes.

To some degree, computer code is process as never seen before. It allows the inscription of a process more intricate than human minds could follow, and the consistency that human hands can’t maintain. It is one thing to create a process that lives in human minds, but something better to create a process fully edified in computer logic. But there are many, many systems which are not amenable to computer automation, such as governments, policy, daily-business operations, and tasks which require more intelligence than currently afforded by non-sentient computers. These systems are ripe for formalisation through processes.

It’s easy to make a bad process, and this gets maligned a lot. But I rarely see the appreciation of a good processes which enables the creation of something that is greater than the sum of it’s parts.

So it’s technically impressive, does this make it aesthetically pleasing? (9 November 2025)

“Expert aesthetics” is a phenomenon I believe to be real, but have been struggling to pin down for a while.

As someone gains expertise in a field, their sense of aesthetics in that field will change: they’ll start to find different things beautiful than what they did when they were novices. Their sense of aesthetics will morph as they grow to see the fine details of the field better, and learn what’s technically difficult to do versus what’s impressive-looking but actually simple.

We can see this with programming; tweaking the colours or border-radii of a website will often draw ooh’s and aah’s from management, but only the most elaborate distributed architecture diagram will gain you points on hackernews. The experts have gained a sense of aesthetics for the things that are technically challenging, in a way that’s different from what a layperson might think is aesthetic.

Is the expert’s view wrong? I don’t know, and I don’t think a fully-general statement can be made. Consommé is a french broth that (I’m told) is fiendishly difficult to keep clear, and even the slightest mishap will turn cloudy (try search for crystal-clear consommé and you’ll see the steps that are taken to avoid this). But is a perfectly clear soup really that much better than a slightly cloudy soup? I’m sure the French chefs would scream at me for even asking the question, and I don’t doubt that they’re tasting subtleties that I miss. But nonetheless, I suspect that their technical appreciation for the skill required to make a cloud-free consommé is being confounded with their aesthetic appreciation for the taste of the finished soup. In a world where they knew not the difficulty, would they appreciate it the same?

This applies to all fields of expertise that I’ve cared to examine, and the impact is a disconnect between the experts in a field and the laypeople outside of the field. This disconnect isn’t problematic, but it becomes visible when experts try to sell their wares. An expert has a different sense of aesthetics to the layperson, and so when they try to craft things that appeal to their own sense of aesthetics, the layperson is unimpressed. But when the expert is demotivated when they figure out what impresses the layperson, because this thing is almost certainly not technically challenging enough to be interesting.

## AI hasn't seen widespread adoption because the labs are focusing on automating AI R&D (8 November 2025) Read on [LessWrong](https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/5Zq9FKfYzcxcwCoRJ/ai-hasn-t-seen-widespread-adoption-because-the-labs-are) | #artificial-intelligence #economics #lesswrong There's been some questions raised about why AI hasn't seen more widespread adoption or impact, given how much better ChatGPT _et al._ are above the previous state of the art for non-human cognition. There's certainly been lots of progress, but the current era of AI is a few years old at this point and many low-hanging fruit which feels doable with current technology is not in fact, done. Given this is what we see, I'm fairly confident that the frontier AI companies are intentionally not pursuing the profitable workplace integrations, such as a serious[^5] integration with Microsoft office suite or the google workplace suite. The reason for this, is _if_ you had a sufficiently good AI software developer, you could get a small army of them to write all the profitable integrations for you ~overnight. So if you're looking at where to put your data centre resources or what positions to hire for or how to restructure your teams to take advantage of AI, you emphatically do _not_ tell everyone to spend 6 months integrating a 6-month-out-of-date AI chatbot into all of your existing products. You absolutely _do_ pour resources into automating software engineering, and tell your AI researchers to focus on programming ability in HTML/CSS/JS and in Python. This, not coincidentally I'd argue, is what we see: most of the benchmarks are in Python or some web stack. There is also a significant amount of mathematics/logic in the benchmarks, but these have been shown to improve programming ability. So what would we predict, if the above is true? I predict that ~none of the labs (Anthropic, Google, Facebook, OpenAI+Microsoft) will launch significant integrations that are designed for immediate business use-cases until either most of the code is written by their internal LLMs or if they see these products as a useful means of collecting data (e.g. Sora). If this is true, then we can also infer that the leadership and stakeholders of these companies (if it wasn't already obvious), is _very_ AGI-pilled, and whoever's pulling the shots absolutely believes they'll be able to build a synthetic human-level programmer within five years. It doesn't say anything about ASI or the AI's ability to perform non-programming tasks, so it'll be interesting to see if the movements of these big companies indicates that they're going for ASI or if they just see the profit of automating software development. While automating AI R&D is an explicit goal of some of these companies, I'm not sure whether this goal will survive the creation of a competent, cheap, human-replacement software developer. Up until this point, the steps towards "automating AI R&D" and "automating software development" are approximately the same: get better reasoning and get better at writing code, using software development tools, etc. But I'd argue that AI R&D is significantly harder than profitable software development. So for now, the companies can use the sexy "we're automating AI R&D" tag line, but once a company builds a synthetic software developer I'm fairly certain that the profit-maximising forces at be will redirect significant resources towards exploiting this new-found power. ## If you're going to arrive late, don't _also_ arrive unprepared (7 November 2025) #practical Being late happens, because life is unpredictable and sometimes you can't foresee everything or the cost of mitigating some risk is just too high. But often I see someone arrive late _and_ be unprepared, frazzled, or otherwise not ready for what they're about to do. I spent some years as a deckhand on yachts in the Mediterranean, and sometimes myself and a crewmate would be tasked with cleaning a particular part of the ship and we'd run late. The guys who'd been working for longer than I had, taught me that if I'm going to be late, I should at least have done a good job. It's even worth being slightly _more_ late, but to have finished the job properly, than to be late and also have the job be incomplete. This applies to other parts of life as well: if you're frantically running to arrive at a meeting, but you get to the door X minutes late, it's _extremely worthwhile_ to spend literally 1 minute to catch your breath, clean the sweat off your brow, and collect your thoughts a bit. Whoever is waiting for you almost certainly won't care about being $X$ minutes late vs $X+1$ minutes late: they just care that **you're late**. But how you walk through the door will set the tone for the meeting, so it's worthwhile ensuring that you've got everything ready, that your heart has calmed down a bit. Make sure that you go into the meeting actually _ready for the meeting_, and not recovering from your mad dash to get there in time. Another example is if you're running late to a party, don't be late _and_ arrive without a gift. Rather be an extra 15 minutes late but arrive with a gift for the host. Of course, this is all a trade-off. Sometimes you can afford to be an hour late, sometimes you really can't afford to be late at all. And sometimes it's really worthwhile arriving prepared, but other times you just need to physically be present and how you arrive doesn't really matter. But I find that people are overwhelmingly biased towards being late _and_ arriving unprepared, as opposed to thinking how to make the best of the situation _given that_ they're going to arrive late. ## The only important ASI timeline (6 November 2025) Read on [LessWrong](https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/pfb57sKG5FLF4wEpR) | #lesswrong #artificial-intelligence There's lots of talk about timelines and predictions for when someone will build an AI that's broadly more capable and intelligent than any human. These timelines range from 2 years to 20 years to never, although pretty much everyone[^3]'s timelines shortened after the publication of ChatGPT and the subsequent AI boom. In the discussion of AI safety and the existential risk that ASI poses to humanity, I think timelines aren't the right framing. Or at least, they often distract from the critical point: It doesn't matter if ASI arrives in 5 years time or in 20 years time, it only matters that it arrives during your lifetime[^4]. The risks due to ASI are completely independent of whether they arrive during this hype-cycle of AI, or whether there's another AI winter, progress stalls for 10 years, but then ASI is built after that winter has passed. If you are convinced that ASI is a catastrophic global risk to humanity, the timelines don't matter and are somewhat inconsequential, the only thing that matters is 1. we have no idea how we could make something smarter than ourselves without it also being an existential threat, and 2. we can start making progress on this field of research _today_. So ultimately, I'm uncertain about whether we're getting AI in 2 years or 20 or 40. But it seems almost certain that we'll be able to build ASI within my lifetime. And if that's the case, nothing else really matters besides making sure that humanity equally realises the benefits of ASI without it also killing us all due to our short-sighted greed. ## Detection of AI-generated images is possible, just not widely adopted (5 November 2025) #artificial-intelligence #ai-art #generative-ai #c2pa The project spearheaded by Adobe, but now implemented by OpenAI, LinkedIn, and others, has the incredibly uncatchy name C2PA. It essentially allows the creator of an image to digitally sign their images, and then embeds that signature into the image in a way that 1. follows the image around the internet when it gets shared and 2. doesn't affect the visual image in any way. Pretty much all image files allow metadata to be attached to the image (like latitude, longitude, shutter speed, etc), and C2PA piggy-backs off of this mechanism to allow a digital signature to follow the image. This is amazingly useful! It allows good actors to verify that a photo came from a reputable source. So if you're a journalist and you take a photo that's politically divisive, you can digitally sign the image as a way of attaching provenance to the image. This does _not_ allow you to identify bad actors, since they can either strip out the C2PA metadata from the image or just take a screenshot of the original image, thus removing any history of the image. But this isn't disastrous; browsers will flash big security-related warning signs if you try to view an HTTP website, which has lead to an assumption that every non-HTTPS website is dangerous by default. We should apply this same thinking to images: all images should be guilty until proven innocent, and social media websites should display images without C2PA metadata with big warning signs indicating that the image is untrustworthy. So what's the problem with C2PA? Just about every social media website strips out all image metadata from the images during upload, as a way of reducing the size and complexity of the image. This means that, while there's reasonably good support for embedding C2PA metadata into your image, you basically can't _send_ that image anywhere without the metadata being stripped out behind your back. I was pleasantly surprised to see that, when I updated my LinkedIn profile picture, it indicated that the photo had C2PA metadata. This is great! I hope this technology gets broad adoption, and that more people come to know that it exists and that it works. ## An AI Manhattan project would look like Ilya, Mira, Karpathy, etc all working on secretive projects (4 November 2025) #artificial-intelligence #manhattan-project This prediction is low-confidence, but _if_ there were an AI Manhattan project going on, it would be tricky to pull off without raising suspicion (moreso than the original Manhattan project, due to the internet). One possible way for the US to get enough talent without raising suspicion would be to have the top AI scientists pretend to start their own stealth-mode AI companies, which is indeed what we've seen. I'm pretty sure this isn't the case, it seems unlikely that an AI Manhattan project would be started given that 1. it would be competing with existing private industry and 2. it would be nearly impossible to hide the project. If the US government did want to achieve the ends of an AI Manhattan project, it seems more likely to me that they'd nationalise the companies at the forefront of the labs, rather than build their own organisation for doing AI research. I guess only time will tell... ## The EU could hold AI capabilities development hostage if they wanted to (3 November 2025) Read on [LessWrong](https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/86NQZFN3SSAomboGv/the-eu-could-hold-ai-capabilities-development-hostage-if) | #lesswrong #artificial-intelligence #european-union It's well-known that the process for building AI GPUs has a hilariously fragile supply chain. There are multiple links in the chain that have no redundancy: - Carl Zeiss (Germany): Supplies optics/lenses for EUV lithography machines - ASML (Netherlands): Produces the EUV lithography machines that make the chips (using Carl Zeiss' optics) - TSMC (Taiwan): Produces the chips (using ASML's machines) - Nvidia (USA): Designs the AI chips Critically, two of these companies are based in the EU, meaning that no matter how much e/acc twitter might laugh at the EU's GDP or bureaucracy, GPT-6 is not getting built without an implicit sign-off from the EU. If the EU felt the need, they could halt export of EUV lithography machines out of ASML and also halt export of any EUV-empowering optics from Carl Zeiss. These companies are within the EU, the EU can do it. This wouldn't halt AI chip production immediately, I'm sure the existing lithography machines would keep running for a while. I'm unsure of how much regular maintenance or repair parts these machines need from ASML employees, but I'm certain it's non-zero. So an EU-ban on exporting EUV lithography wouldn't halt chip production immediately, but it would inevitably bring it to a halt over time. Banning the export of EUV machines would be a gutsy move, for sure, but it's entirely possible. And as tensions raise, it only become more likely. Not many countries have the ability to hold the AI-capabilities world hostage, but through a bizarre twist of fate, the EU is able to do just that. I'm unsure of whether they're aware of the power they have, given how bloated their bureaucracy appears from the outside. But this is an ace-up-their-sleeves that 1. exists, 2. could be played, and 3. isn't going away any time soon. ## AI Safety has a scaling problem (2 November 2025) #artificial-intelligence #field-building #scaling #practical #policy AI safety research is (mostly) done via fellowship funnels that filter out the population of the internet down to people who have shown they can do AI safety research. This process works well, but requires one-on-one mentorship from academics and researchers, and thus cannot scale. Anthropic recently had a fellowship position for which they accepted 32 people, from a total of 2000 applicants (that's a 1.3% acceptance rate). MATS mentors were recently talking on twitter about the absurdly high qualifications of the applicants. High bars are good, but it's _not good_ that people who can do AI safety are not in fact doing AI safety. This is a resource constraints problem, and deserves attention to fix it. I've got ideas for a AI research bounty, in which anyone can submit cash prizes for completing some well-defined work, and then anyone can submit completion of that work and receive the prize. But a greater description will have to wait for the full essay. ## When to be risky and when to be safe (1 November 2025) #explore-exploit #maximising-your-mean #practical There's a trade-off that's often made but rarely considered, and best described through the analogy of dating: when dating to marry[^1], you see some people attempt to make every date go well, and try to ensure everyone they date will like them. This seems like a reasonable goal, but I fear it collapses every potential date into a point, as though they'd respond identically. If everyone reacts the same, then it's reasonable to play it safe and attempt to please everyone. But that's not the case, in reality 1. everyone reacts to different things in different (often conflicting) ways, and 2. you _don't care_ about making everyone think you're a chill dude (a mediocre response), you care about ensuring _one person_ thinks you're the best person on the planet (an extreme response). You will not get an extreme response by attempting to please everyone, you must be specific enough that you displease many people in order for you to maximally fit with one person. This applies more generally: you can either pursue a strategy to optimise your "median" performance (never having any terrible experiences but also never having any amazing experiences), or you can optimise your "maximum" performance (often having bad experiences but occasionally having amazing experiences). The difference in your optimal strategy comes down to the cost of failure, the number of good outcomes you need, and the bar above which you succeed[^2]. When building a start-up, you cannot afford to play it safe, because if you take "normal" decisions then you'll end up like "normal" start-ups, which is to say that you'll go out of business. You _must_ be weird, and take big risks, because the bar for success is above the median performance. You don't need to figure out the right way to run a business a hundred times, you just need to do it once. So exploration trumps exploitation (in this example). Likewise for finding a job, you just need one company to give you an offer, you don't care about a hundred companies thinking you're a nice guy but not quite what they're looking for. You'd rather 99 companies think you're not a good fit, but one company think you're perfect, than have 100 companies think you _might_ be a good fit. "Might be a good fit" does not get you hired. [^1]: Or otherwise with the intention of settling down with someone for more than ten years. [^2]: I'm pretty sure these are all the same or equivalent, but I'll explore these ideas in a full essay [^3]: everyone referring to everyone who's watching AI developments and progress [^4]: or the lifetime of the people you care about, which might include all future humans. [^5]: There do exist MS office/google workspace integrations, but they're about as minimal as you can get away with and still the pointy-haired managers "yes MS office 'has AI'". These integrations are not serious, they are missing a lot of very basic functionality that leads them to be little better than copy-pasting the context into your chatbot of choice. [^6]: because there are many different sign languages [^7]: I'd consider this unethical, and maybe you too would consider this unethical. But given that factory farming is _real_, and this post is entirely hypothetical, I'm not going to consider the very significant ethical issues at play here. [^8]: Okay, Apple doesn't _really_ innovate much nowadays, but it made sense when I first started thinking about this quandary. And you're smart enough to see through the example to my core argument (right?).